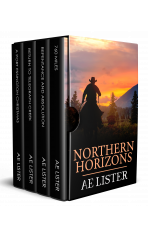

The stench of Dawson City hit me before anything else. My wagon full of supplies for Mr. Henley had merged with more traffic several miles before, so I must have been getting close to civilization—or what passed for civilization in these here parts.

And by more traffic, I only meant there was one other wagon and a couple of horses with riders on the road ahead of me. Most who traveled this country in the summer months used the river systems instead of picking their way through the tricky overland passes and uneven ground.

I liked the risk of it, seeing as how this was a safer way of living than anything I’d done o’er the past twenty years. I was traveling the straight and narrow now, trying to be an honest, hardworking man. I’d wasted the glory of my youth with a band of no-good thieves and murderers, doing their dirty work for nothing but a smile and a kick to the trousers. Yeah, I’d had a place in the world, but it hadn’t taken long to realize t’wasn’t a good one. Problem was, it had taken more time to figure out how to leave that life behind than it had to realize that I wanted to.

But I had found a way out, and my theories on how much I was worth to them had been correct. Nobody had lifted a finger to find me. I was nothing to them and always had been. Spook, Whitlaw and the gang were rotten, immoral men who used folks then tossed them aside when they weren’t of use no more—or simply didn’t care if those people decided to quit them.

Even though it stung, since there’d been a time that I’d imagined they’d liked me and maybe thought of me as a valuable addition to their circle, t’was a blessing. Because if either of them had decided t’was in their best interests to get me back into the gang or to make sure I didn’t go joining any other gangs, I would have been disposed of a long time ago. But I figured they didn’t care one way or another what I was doing now, and they’d probably rounded up a couple of greenhorns to train into the life the way they wanted, doing their dirty work and being witness to more cruelty than they could ever imagine.

Now I was hauling supplies on the regular by way of the Overland Trail and doing it for less money than Mr. Henley would pay a riverboat captain. It didn’t leave much extra for me, but it paid for keeping up the horses and the wagon, gave me something to do that I enjoyed and a way to be my own boss. My life was my own, small as t’was, and I was eternally grateful for that.

T’was rough terrain I traveled, and there were wild animals that would kill me if I wasn’t on the lookout. But I loved this country, and I knew it from twenty years of roaming and outlawing with the gang before I’d left that life in the Yukon dust.

The gold rush that had mobilized half the continent was long o’er, and most of the folks left were simply hanging on. To what, I wasn’t rightly sure. I’d been delivering supplies to Mr. Henley for a couple of years, since 1904, and ‘The Paris of the North’ had long since failed to live up to its name. The city just kept getting dirtier and the people more desperate. What little economy was left centered around small shops and mining operations that remained, trying to make sense of a world where towns were built up then abandoned in the blink of an eye, when better offerings were found elsewhere.

The city was on the decline and full of desperate people.

There were one or two decent hotels left, so after I’d unloaded the wagon at Mr. Henley’s store with the help of his son, I made my way to the Miner’s Rest Hotel on Front Street in the middle of all the action. By ‘action’, I meant the dubious operation of a number of saloons and cathouses that were left o’er from the gold rush days. But, where they might have enjoyed a brief time of luxury and the illusion of respectability, now they languished in a sorry state of lefto’er offerings and a dank sense of necessity.

There were still miners in and around Dawson City with gold to spend, but they were few and far between, and a far cry from the gold dust that had flowed for a few years at the end of the century. That gold had made this city, and now t’was dying without it. T’was a shadow of its former self, and I knew that because I’d seen it at its height, back when I’d been with the gang. We’d make the occasional trip into town after a good job and spend our money on whores and liquor.

The whores in those days had been personable, intelligent and outspoken women—lots of them pretty, many of whom were in Dawson to mine the gold out of the miner’s themselves, make their fortune on their backs and head back to the places they’d come from, to lead respectable lives with no word as to how they’d gotten their money. They were a special breed, these young women, hardy and enterprising. But they’d left to follow the gold and the miners to Alaska when the pickings got slim in Dawson, and now the only ones left were the ones who had no other choice but to do the work they did. I’m not saying a man couldn’t find a good one, and some of the cathouses had higher standards than others in terms of cleanliness and the way they did business.

But things were different now, and the town was dying of neglect.

Even as I stabled the horses and left the wagon in the care of a stableman at the hotel, I saw a young fella in grimy clothes and worn shoes swipe an apple from where it sat on the wagon bed, where it must have tumbled out of one of the boxes I’d delivered to Mr. Henley. T’was hard to guess his age under all the filth—probably an adult, although barely. He looked awful young to me…and scraggly.

I met his gaze, and he froze like he thought I’d go after him or mention him to the stable hand. But I wasn’t gonna do that. I held his wary gaze for a whole second, trying to let him know I didn’t have anything against him, and I wasn’t gonna tell anyone about the apple. He narrowed his eyes at me as his grimy hand tightened around the bruised fruit, and he took it and turned tail, moving fast into the street so he wouldn’t get caught if I changed my mind.

A shiver snaked down my spine because I’d seen a desperate look like that before. Those eyes knew pain and abuse, hunger and hopelessness. I hated everything about those eyes and what they meant—that this youngster was reduced to the most basic of human needs and even those weren’t being met. But I shook it off, because there was more than one desperate, starving fella in this town, and I couldn’t do anything about it. And there wasn’t no use worrying about any of them.

In the hotel I paid for a large room with a double bed because I had the money and I was sick of camping on the ground. Mr. Henley had paid me and given me a bonus because he was pleased with my punctuality and the quality of the goods I’d delivered. So, goddammit, I was gonna spend a few days living in style.

First off, I needed a bath then a meal. Then I was gonna get myself a whore and fuck all the hardships of the past few weeks of rough travel out of my system.

* * * *

The hotel maid had two young men bring up a tub and three buckets of hot water, which they poured into the tub before leaving. The maid herself brought a bucket of cooler water for rinsing and left it on the floor beside the tub, giving me a towel and a bar of rough soap.

“Anythin’ else you need, mister? And don’t say a woman, ’cause you can get one o’ them down the street and I ain’t got nothin’ to do with that.”

“No, ma’am. I only need what you brought me—and thank you for that.”

She huffed, as if she didn’t believe me, then left me to myself.

It felt good to take off my dirty clothes and leave them outside the door for the maid to wash. I had some clean ones in my pack that I got out and set on the chair for after my soak. I stretched to one side, then the other, making my old bones creak in the process. I was thirty-six and had wasted most of my life doing things I wasn’t proud of. How I’d got myself involved with the likes of Spook and Whitlaw was an old story of misguided loyalty and misplaced trust. They’d impressed me with their skills at shooting and robbing before I’d been introduced to the coldness with which they dispatched their victims in the name of completing a job. Spook especially had a tendency toward torture that I’d found extremely off-putting. But by the time I’d realized the depths of their depravity, t’was too late. I was a fixture in the gang, and I didn’t know how to escape it.

I was valued for my strength and my willingness to do whatever they asked of me, no matter how humble. For the longest time I’d thought they’d hunt me down if I left and either kill me or drag me back, until I realized that they didn’t even care enough to do that. T’was a cruel joke to me when I’d finally gotten the balls to take off and leave them, that I could have done it ages before without a problem.

They’d ruined my life and for what? For nothing. My presence in their gang had meant nothing, only that I bore witness to the cruelty and carelessness of evil men with no solid plan for the future. They were aimless, simply living for the next job and the next—killing, raping and torturing for the privilege of scrounging a few dollars that they soon spent on drink and women.

T’was a rude awakening for me that life was only what you made of it.

And I was determined to make something of mine now.

* * * *

I slept the sleep of the dead that night and woke up late the next morning. All that travel had worn me out. I hoped the horses were recovering with good feed and attention in the hotel stables. They’d need a few days’ rest—and so would I.

I popped in after breakfast to check on them.

“Hey, there. My horses doin’ okay?” I asked the lad in charge of the stables.

“Yes, sir. They’ve enjoyed their time to rest, and I reckon they’ll be ready to go by tomorrow or the next day, sure enough.”

“Good. I know you take good care of ’em.”

Dixie, the brown mare with the stripe down her face, was the only thing I’d got worth any value from my time with the gang. I’d worried they’d come after me to get her back because she was a damn good horse, strong and young enough to have a lot of good years left in her. But the gang had enough horses, and they could always get more since they had no problem stealing anything they took a shine to. They probably figured t’was more bother to chase me down than to find a random horse if they needed one.

As part of our contract, Mr. Henley paid for their stabling and me a salary to bring goods from the depot in Whitehorse to Dawson. It saved him a couple of hundred to bring them supplies overland rather than pay the high prices of river transport. He owned a sleigh that I used in the winter months, and t’was a cold and harsh journey, except for the roadhouses that were scattered along the trail where I could get a warm bed, a couple of hot meals to shore me up and shelter when the weather was bad. I was getting used to it, but I still didn’t look forward to the cold and dark of a Yukon winter. Still, t’was good, honest work and I was living a respectful life.

That in itself was worth its weight in gold.

I reckoned I had one more trip with the wagon left before I’d have to switch to the sleigh. Winter came early up north, and t’was late August now. By mid-September to early October, temperatures would plummet, and the snow would come, coating everything in a frigid white blanket and bringing the threat of frostbite and hypothermia with it. Still, I was happier with the weather trying to kill me than I ever was treading lightly around Spook and Whitlaw, who could’ve murdered me for the heck of it at a moment’s notice. The weather seemed more honest and predictable than them two.

While I leaned against the stable door, I saw that young man again—the skinny one covered in dirt and grime with the tragic eyes and likely more tragic backstory. This time he slunk along the side of the mercantile across the street, eyeing a pretty girl in a coat and bonnet whose purse dangled by strings from her dainty wrist. There weren’t a lot of respectable women in Dawson, but she was one of them, and it looked like she had the wealth to keep her place in society.

I stood up straighter, narrowing my eyes at the wraith, trying to tell him with a look that he was getting in o’er his head with her. She wasn’t gonna let a dirty street rat steal her money, and if she caught him red-handed, she’d have the law on him in a heartbeat.

I caught his eye and shook my head once back and forth, like I was his daddy telling him to behave himself, but he didn’t pay any attention—only licked his lips and focused in on that lady’s purse, inching toward her as if he’d be able to slip it off her, when t’was tied on fast with a pretty green ribbon.

I rolled my eyes and stepped forward, crossing the street quickly and doffing my hat. “Ma’am,” I said, attracting her attention as the street rat’s eyes widened and he shrank back. “Sorry to bother you but watch your step. There’s a nasty puddle here in your way. Allow me to help you,” I said, putting on my most gentlemanly manners to assist her when she was perfectly capable of making her way along the street without my assistance.

“Well, aren’t you kind? Thank you so much, Mister…?” Her brown eyes flashed up at me with a query.

“Downing. Jimmy Downing,” I said, glancing at the skinny fella who’d melted into the shadows with an angry frown.

I let the lady take my arm and guided her around the puddle. She let go and flashed me a smile. “Thank you. Good day,” she said, releasing my arm and walking off as I moved back along the street to the last place I’d seen the young man.

I found him huddled in a doorway, regarding me warily with blatant hostility.

“Why’d you do that? That was my mark, and you knew it.”

“What’s your name, boy?”

“I ain’t a boy. And I ain’t gonna tell you my name.”

I took a breath. “Why don’t you come with me, and I’ll get you somethin’ to eat. You look hungry.”

“Yeah? Well, you look like you enjoy gettin’ in the way of other people who’s just tryin’ to get by.”

I narrowed my eyes. “If you’d gone after that lady’s purse, she’d have called the law on you. That what you want?”

He sighed, and it looked like a shudder went through his wiry frame. “Don’t matter. Why don’t you leave me be?” He sounded so tired and about done with everything, so it seemed futile to continue.

“Fine. Suit yourself.” I moved off and went about my business, done caring about what happened to the dirty little bastard. He’d said he wasn’t a boy, and I’d figured that, but he didn’t look much older than eighteen or nineteen, in my opinion, and what was the point of arguing, anyway? I’d offered to get him some food and he’d declined, so that was that.

I had some small errands to do, and t’was mid-afternoon by the time I made my way along Front Street to the old Monte Carlo theater, which, in its heyday, had been the star attraction in Dawson City, where many a lucky miner had squandered his gold on entertainment and loose women. Now t’was a run-down, dirty establishment that housed a slew of working women who, while not the cream of the crop of young dance-hall girls that had plumbed the pockets of the miners, but who were a step above what I’d find a street or two o’er in Paradise Alley and Hell’s Half Acre.

The front room was a saloon where a man could grab a cheap drink before heading to the back and availing himself of meatier offerings, and t’was where I planned to spend a relaxing minute or two before satisfying the hunger that had built inside me for weeks. There were brothels in Whitehorse, sure enough, but they weren’t as plentiful as here, and t’was harder for respectable men—or men who were trying to become respectable—to avail themselves without drawing the attention of a disapproving public.

Here in Dawson City in 1906 nobody cared how men spent their time, because things had been so wild and unhindered in them gold rush days. This was a sorry and desperate town now, and the people who lived here had lower standards than most—or could turn a blind eye easier. So I saved my whoring for Dawson City, even though I could have used a more regular relief than waiting for two or three weeks to pass between a brush of the intimate kind.

As I trod the wooden sidewalk in the fading afternoon light of a late August afternoon, my head was filled with the delights soon to be available to me, and I wasn’t prepared for the sight of the disheveled street rat lurking in the shadows of the doorway as if he were about to go in himself.

-148x237.png)